Zayde

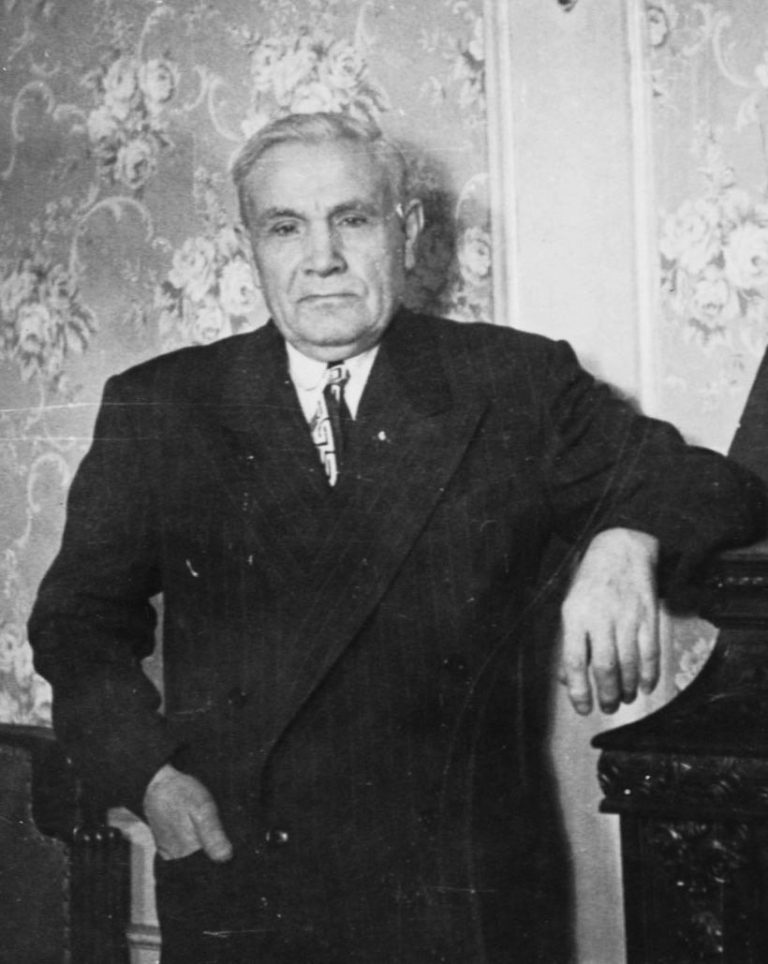

Zayde – the Yiddish term for grandfather – was a handsome man with bright blue eyes, a thinning stock of talcum-white hair, a strong chin, and a stiff and dignified pose. His language of choice was Yiddish although he could also speak Russian, Polish, and several other Slavic tongues. His English, what there was of it, was infused with the guttural sounds of Eastern Europe and barely comprehensible. An inability to communicate in the language of his adopted homeland was a continuing frustration, particularly because he valued learning, considered himself an intellectual, and loved nothing more than to argue arcane points of philosophy, politics, and religion with whomever he could.

Born in 1886, as an eleven year old he had abandoned his parents and birthplace in Stolin, a tiny village in the extreme southern part of present day Belarus, to learn a trade, escape poverty, and, ultimately, to become a terrorist. As a boy I vividly recall being shown a yellowed photograph of him that had been taken somewhere in Eastern Europe a few years before the turn of the century. Accompanied by two young revolutionaries who were armed with pistols, he held a knife in one hand and a hangman’s noose in the other. The contrast between the kindly, intellectual grandfather I knew while growing up and the young hoodlum in the photograph was shocking.

Zayde‘s political leanings then, and throughout his life, were to the extreme left. He came by that view because of the paltry wages, long hours, and unsound working conditions that he and his fellow workers endured. In a search for remedies, as a young man he had joined the “Brothers and Sisters”, a forerunner of the Jewish Labor Bund (in turn, an offshoot of the Socialist Labor Party) and had been arrested at one of their numerous demonstrations in Pinsk. Undaunted, upon his release he made the long journey to Ekaterinoslav in the Ukraine to resume his revolutionary activities. He became a socialist, a Menshevik, and was soon arrested for a second time. Some years later, still committed to the cause, he journeyed to London, where he continued his work for the Bund while training to be a tailor. He was to return to Belarus once more, this time to marry and start a family.

At the time, Russia was in turmoil. In 1905, thousands of workers and peasants had peacefully marched in St. Petersburg to petition Czar Nicholas II at his winter palace ion an effort to improve conditions. On “Bloody Sunday”, the Czar’s imperial guards fired on the crowd and killed scores. An uproar ensued. That event, together with Russia’s humiliating loss to Japan in the Russo-Japanese war combined to weaken the power of the central authorities and throw the country into chaos. Revolutionary groups of all stripes became increasingly active. They fought against the regime and battled each other in the streets. As they had for many centuries, Jews became scapegoats of radical mobs intent on punishing those who they believed were responsible for the country’s travails.

Zayde, as a young man eligible to be conscripted into the army, was concerned for both his own safety – it was common knowledge that Jews were placed on the front lines and used as canon fodder – and for his family’s. To escape serving, he shot off a pistol near his head and punctured an eardrum. But the dangers persisted. Remaining in Russia was no longer an option. In 1911 he emigrated to America. He left behind a wife, my bubbe, and a young son named Harvey (my uncle who died before I was born). I’m not certain that he was aware that my grandmother was pregnant with my father, who apparently was conceived shortly before zayde left for America. Zayde‘s plan was to labor in the sweatshops of New York as a tailor and accumulate enough money to pay for passage for his family to the United States. It took three years for him to save up the required sum so that bubbe and her two sons could make the voyage. When they arrived, my father, not yet three, didn’t recognize the stranger who greeted him at Ellis Island. He began to wail. It was a source of great sorrow for zayde that his young son treated him with fear and suspicion for many months after his arrival in the new world.

Zayde was born into a fervently religious family, but after he left home, he, along with many of his fellow socialists, abandoned their faith. The Bund was anti-Zionist and zayde adopted that stance as well. But he changed his mind between the time of his arrival in America and before he retired. He became a staunch Zionist, a strong supporter of Israel. And, like many older folks he found religion. My father, who had a decidedly agnostic streak, regularly teased his father about his prior religious beliefs. Zayde, briefly disconcerted, would redden and sputter, helpless in his weak command of English. But religious he had become, to the extent that he was capable of discussing some of the most obscure points of Jewish lore with members of the several synagogues he regularly attended.

Because I was so proud of my grandfather, I considered the charges against him, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, unwarranted. Then, unexpectedly, some additional data turned up. My cousin Helene sent me an article from a book, “A Thousand Years of Pinsk” that carried a brief biographical sketch of zayde. Published in 1941, the book chronicles the history of Pinsk, a city that had a large Jewish population until the Nazi occupation in the 1930’s when nearly all the Jews were shot and dumped into a mass grave – 10,000 of 25,000 in one day. It was where zayde had lived and worked for several years in the early 1900’s. Written entirely in Yiddish, in Hebrew characters, the book has a section describing some prominent Jews who had come from Pinsk and had settled in the new world. I found the page that was devoted to my grandfather. He was easily recognizable in an accompanying grainy photograph. Helene had the page translated and sent a copy to me. Some of what I learned I have included in this chapter.

I was so intrigued that I purchased a copy of the book even though I knew I wouldn’t be able to understand more than a few words. To my surprise, two pages away from zayde’s entry was a similar one about a Rebecca Cohen, apparently a fellow refugee from Pinsk (The text in the article calls her “Rebecca”, but the caption under the photo says “Becky” in Yiddish). There seemed no doubt that this was the woman that my grandmother cursed habitually. Accompanying the article was a small grainy photograph. It showed an attractive dark haired woman with a long, and I imagine, an impressive biography. Even with my limited grasp of Yiddish I could make out that she belonged to several Socialist groups and was an active member of the Workman’s Circle. Tellingly, she was the only woman in the entire book who had a biographical article devoted to her. Of course, the piece didn’t settle the issue that I was interested in. I still didn’t know if my grandfather broke his marriage vows. But if he did, the evidence suggests that the temptation must have been very great.

Many years later, at bubbe’s funeral, my sister, Elaine and my cousin, Helene, spotted a woman that they thought was Becky standing apart in the back of the crowd of mourners. The two looked at each other knowingly, simultaneously whispered the incantation that they remembered so well to each other, and burst out laughing. My grandfather didn’t see her, or if he did, he didn’t acknowledge her existence. Perhaps it wasn’t Becky.

After I came of age, zayde took it upon himself to try to persuade me to become religious. Even then my convictions were were of a scientific nature and I resisted. However, he didn’t gave up trying. I vividly recall one warm late September day when he took me to his schul (synagogue). It was on a high holy day, Rosh Hashanah, the celebration of the Jewish New Year. I must have just turned 13. The synagogue was a block from the el, a half mile west of our house in an area close to the Brownsville section of Brooklyn, a neighborhood that was even poorer than our own.

The pitiful and largely unmarked house of worship where we were headed was barely distinguishable from the surrounding brownstones. Around the front stoop stood a gaggle of old men, dressed in their best attempts at their holiday finest, wearing their yarmulkes (skull caps) and tallitot (prayer shawls), gossiping and gesticulating in Yiddish and accented English (In my younger years, everyone that I came into contact with over the age of 50 spoke with a European accent. When I left New York, I was shocked to find older people who didn’t sound like refugees from Eastern Europe) . But the tumult outside was nothing compared to what was going on within.

I’ve observed services in a variety of religious venues, but what I encountered when I accompanied zayde to schul was a distinctly different experience. We were in a large undecorated dimly lit room that was a few steps below street level crowded with old men smelling of tobacco and of pickled herring that they had eaten for breakfast. In the center was a raised wooden platform – the bimah – bordered by a railing. Standing on this platform were several important personages: the rabbi, the cantor, and other distinguished congregants. Surrounding the bimah were rows of benches crammed with men who were davening: swaying back and forth while muttering the liturgy in Hebrew. There were no women in evidence; they were hidden, segregated from the men behind a curtain in the back of the synagogue.

To my surprise, each member of the congregation appeared to be at a different place in the prayer book. And while most prayed noiselessly or murmured quietly under their breath, at times an enthusiastic parishioner would encounter a passage that he particularly admired and would raise his voice in the sing-song chant characteristic of Hebrew prayer. It was chaos. Adding to the pandemonium, as each new congregant arrived, he would greet his fellows loudly and enthusiastically, with little regard to the prayers being recited or to the elders stationed in the center of the room. They, however, seemed dismayed by the racket. One elderly gray beard who seemed to be in charge of keeping order regularly shouted the Yiddish equivalent of “Be quiet!” at the top of his voice while pounding a book with the palm of his hand, but it had no discernible effect and only added to the din. Occasionally, the noise level dropped when a particularly beautiful prayer was sung by the cantor. At times, everyone would rise simultaneously when the leaders would come to a passage that apparently required standing. But for the most part, bedlam reigned.

Zayde was at home in this element. He greeted several old acquaintances warmly in Yiddish, wishing them a happy and healthy new year. They seemed to regard him with respect, calling him Mr. Shaeffer, a slightly altered version of our family surname. He preferred to be called “Safer”, a Hebrew word, usually spelled “sefer”, meaning book. My father used the name “Sofer”, a word derived from “sefer”, that means “scribe”. The circumstances that caused this generational name shift are unclear, although some in the family thought that it stemmed from a typographical error when my father entered elementary school. I remain a “Sofer”, and my sons and grandchildren bear the same name.

I was startled to see Arnold, a classmate, in the middle of one isle, silently and expertly davening like the old men. He was one of the few youngsters in this congregation of ancient Eastern European immigrants, and he seemed very much at home. For a brief moment, I envied him. I regretted that I really didn’t belong, that I wasn’t familiar enough with the services to carry on as facilely as he did. I thought it must be a comfortable feeling to be an insider, a solid member of the club, who knows the prayers and melodies by heart, when to stand and sit, and how to properly respond at various points during the proceedings. My shiny silk tallit (prayer shawl, singular) that hung around my shoulders, that had been gifted to me when I came of age at 13 – worn on that day and this but never after – marked me as alien, an outsider, an intruder. While I was not entirely ignorant of Jewish ritual, having taken three years of classes that prepared me for bar mitzvah, I could only sound out Hebrew words, slowly and with difficulty, with no understanding of their meaning.

Nevertheless, of my life’s religious experiences I was most moved by this one. It stood in stark contrast to the orderly, dignified, in some ways sterile goings on in other religious venues that I had attended. It seemed to demonstrate that the liturgy doesn’t need to be accompanied by music, that prayers need not be said or sung in unison, and that services don’t have to be orderly in order to engender a deeply moving experience. The prayers that were recited in that old synagogue were intimate and personal conversations between believers and their beliefs. I sometimes muse that if I wasn’t an atheist, I would join an orthodox synagogue, although, unfortunately, ones similar to that which my zayde and I attended have long since disappeared.

Zayde and I left the service together and walked slowly home side along side one another. It was a lovely early fall day, cool, clear, and with just a few threads of white marring the sky. The streets were deserted. Most people were home preparing for the evening holiday meal. A bare whisper of onion and garlic odors issued from the open windows we passed. Zayde questioned me about our shared experience at the service. That quickly shifted to a discussion about my faith or lack thereof. I explained to him that I planned to be a scientist and that I saw no need to believe in an all powerful God to explain the workings of the universe (a point of view that hasn’t changed over the years). He responded with an argument that he was to repeat to me many times when we had similar discussions, that scientists were so ignorant that they couldn’t even decide which came first, a chicken or an egg. He, of course, was right. Origins of all kinds are difficult for scientists to confront. They’re more easily dealt with for those with a religious bent because religious doctrine doesn’t require physical evidence. As I couldn’t come up with a suitable counterargument, and because I thought it inappropriate to question his faith on that special day, I didn’t respond. We walked silently together the rest of the way home, both of us exploring our own thoughts. He seemed satisfied that he had triumphed with an argument that I couldn’t best. I felt disoriented. The feelings aroused by the strange but emotional religious experience to which I had just been exposed left me confused. But I think both of us felt strangely fulfilled. We had shared an important moment. Our relationship had strengthened. I think of that day with pleasure.