Tiger

My father went by many names. His friends from his childhood called him “Tiger”. To his two sisters, he was “Izzy”, short for “Israel”. To nearly everyone else, he was “Irving” or “Irv”, probably a name given to him by some anonymous agent when he arrived at Ellis Island. I called him “Dad”.

He had been born abroad, on 11/11/1911, somewhere in the Russian Empire. I never discovered the precise location and can only imagine the circumstances of his birth. Bubbe was alone, caring for a young son, her husband across the ocean. Perhaps she was living with her parents or with other relatives when the birth occurred. In any event, it’s likely that my father was born in a hovel, without benefit of a doctor. Hospitals weren’t a feature of the shetls of Eastern Europe. But regardless of the circumstance of his birth, he proved healthy enough to make the arduous passage across the Atlantic at the age of two.

After the family disembarked and reassembled in New York City, they, like tens of thousands of European immigrants, moved to the Lower East Side, a teeming neighborhood of tenement houses in lower Manhattan. Some years after my father’s death in 1987, Gail and I got a chance to visit the Tenement Museum. Located on Orchard Street, just a few blocks from my grandparents’ former home, it is housed in a building similar to that in which they lived, a grim monument to their poverty.

After the family disembarked and reassembled in New York City, they, like tens of thousands of European immigrants, moved to the Lower East Side, a teeming neighborhood of tenement houses in lower Manhattan. Some years after my father’s death in 1987, Gail and I got a chance to visit the Tenement Museum. Located on Orchard Street, just a few blocks from my grandparents’ former home, it is housed in a building similar to that in which they lived, a grim monument to their poverty.

Tenement properties were generally four or five stories high, with a commercial establishment on the ground floor. There was no elevator. Each floor housed four apartments arrayed along a long narrow central corridor, a so called “railroad flat”. There were two communal bathrooms per floor. On the front side of the building were iron platforms and ladders, fire escapes, onto which the inhabitants could escape the summer heat. While housing laws passed in the early part of the century prohibited apartments without exterior windows, the adjoining buildings were so close together that little sunlight ever make its way into the interior.

The Lower East Side was a neighborhood where the various ethnic minorities lived in enclaves, just a few blocks apart from one another. There was some animosity among these various groups, and my father’s daily trip to school often meant running a gauntlet of young minor league thugs. It toughened him. He learned to use his fists, thereby earning him the nickname “Tiger”. And he not only had to protect himself, he was given the responsibility of taking care of Harvey, his older brother, who was something of a dandy, a dreamer, and an intellectual.

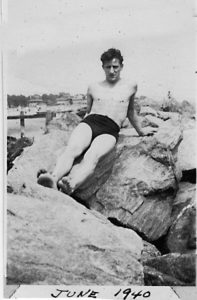

Dad was an accomplished athlete, excelling at basketball and a variety of games played on the New York City streets. In high school, he participated in several cross country races, earning medals that my sister has stored somewhere. Zayde felt that running through the streets in one’s “underwear” was unseemly, but that didn’t deter my father. He also had a short and unsuccessful career as an amateur boxer. I suspect that getting knocked out several times may have contributed to the Alzheimer’s disease that he contracted in his 70’s.  A series of manual labor jobs in his teens as well as the training he undertook for his boxing helped him to become remarkably strong. Many years later, when he was over 60, he would entertain my two sons by flexing his powerful pectoral muscles and biceps. He would challenge them to punch him in the stomach, as hard as they could. It was like hitting a wall. My kids loved it.

A series of manual labor jobs in his teens as well as the training he undertook for his boxing helped him to become remarkably strong. Many years later, when he was over 60, he would entertain my two sons by flexing his powerful pectoral muscles and biceps. He would challenge them to punch him in the stomach, as hard as they could. It was like hitting a wall. My kids loved it.

When Dad’s brother Harvey graduated from high school, he ran off to Texas with a girl friend. After a few weeks on the road, he telegraphed back home; he had spent all of his money. Zayde sent him a single railroad ticket. I don’t know what happened to Harvey’s young friend. Harvey contracted a kidney ailment sometime shortly after his return and passed away. Dad, now the eldest son, had to take on some added responsibilities. Always a little wild, he had to settle down. He had been seeing a woman for several years. She wanted to get married. He wouldn’t commit. One day, she announced that she was pregnant, and that she and Dad “had” to get married. Dad denied having relations with her. Zayde believed him. He insisted that she be examined by a doctor. It turned out that not only wasn’t she pregnant, she was, according to the doctor, still a virgin. Shortly thereafter, Dad met my mother, and they got married.

Dad was the first in his family to go to college. Always facile with numbers, he attended NYU in the early nineteen thirties and earned a degree in accounting. But he never practiced. It was the depths of the depression, and the only job he could find was in the fur business. He soon became a partner in a firm that specialized in muskrat coats, the poor woman’s mink. Later he would start his own small business selling more upscale furs. He would bring them home and have my mother wear them in order to generate business.

When I was about thirteen, Dad decoded that I needed some work experience. We took the IRT subway line into Manhattan to his workplace. in the fur district every day for a couple of months in the summer. The train ride into the city offered an opportunity for us to talk and we became closer. I learned, to my surprise, that he was virtually devoid of ambition. He would tell me that his only goal was to make enough money to support his family. He didn’t want to become rich. He was also extremely modest. His friends would brag about their conquests, with women and in business, but my father would listen respectfully and not respond in kind.

When I was about thirteen, Dad decoded that I needed some work experience. We took the IRT subway line into Manhattan to his workplace. in the fur district every day for a couple of months in the summer. The train ride into the city offered an opportunity for us to talk and we became closer. I learned, to my surprise, that he was virtually devoid of ambition. He would tell me that his only goal was to make enough money to support his family. He didn’t want to become rich. He was also extremely modest. His friends would brag about their conquests, with women and in business, but my father would listen respectfully and not respond in kind.

One incident that occurred late in that summer was revealing in light of later events. We were walking to the station when we spotted one of my friend’s fathers. A short man, dressed in a dark suit, he was shuffling along slowly, dragging his feet, taking tiny unsteady steps, apparently a victim of Parkinson’s disease. Dad leaned over to me and whispered, “If I ever get like that, shoot me. I don’t every want to live like that.” That remark came vividly to mind some thirty years later.

My father retired in his mid 60’s. His timing was not particularly auspicious. There had been a downturn in the ever cyclical fur industry, and he didn’t get as much money for the house my mother and he owned or the business he ran as he expected. Nevertheless, they had more than enough funds to purchase a small house in Tamarack, Florida, a suburb of Fort Lauderdale. At first, they enjoyed their new surroundings. Many of their friends from New York had moved to nearby communities and they pursued an active social life and traveled extensively. But within a few years, at about the age of 70, my mother began to complain that my Dad was behaving strangely. Uncharacteristically, he started arguing with her, complaining that she was treating him like a child, always telling him what to do. When he came up to New Jersey for my son Doug’s Bar Mitzvah, there was clearly something wrong. He’d ask the same questions repeatedly. He’d wander off and get lost. When he got back to Florida, he damaged a car while backing out of a parking spot at the mall, and didn’t report it. The police came around but he had forgotten the incident. They weren’t sympathetic. There were other indignities. Mom took him to see several physicians and it soon became apparent that he was afflicted with some variety of dementia, probably Alzheimer’s disease. The disorder gets progressively and irreversibly worse with time, and the course of my father’s ailment was no exception. Soon Mom had to hire someone, a treasure of a man named “Ruby”, to help look after him so that she could earn a bit of respite from the constant care that he required. I would try to get down to Florida as often as I could, but I wasn’t of much use. Eventually and reluctantly, she asked me to help her put my father in a nursing home.

It was a day that lingers in memory, but one that I wish I could forget. The Alzheimer’s care home that Mom picked – the best available – was gray and dirty, smelling of urine and feces, filled with ancient husks of people slumped over in chairs, their eyes fixed in place, unaware of their surroundings. Dad was placed in a wheel chair and tied down with straps so that he couldn’t wander off. What was most sorrowful for me was his reaction to these offenses to his person. He didn’t resist or try to break free. Instead a sly smile slowly spread across his face and he began maneuvering the chair around the room. He saddled up to a nurse and tried to pinch her rear. A proud vibrant adult had become a child. I cried.