L-DOPA and Carbidopa

7/10/23

I’m going to begin writing about the molecular basis of Parkinson’s with a discussion of the medication used to manage the condition, the ‘gold standard’ of Parkinson’s therapy: L-DOPA/carbidopa.

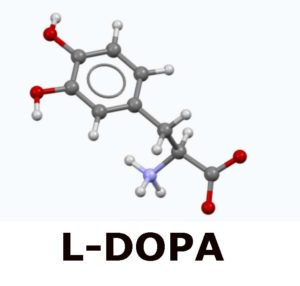

L-DOPA, aka levodopa, is an amino acid whose real name is L-dihydroxyphenylalanine. For those of you who have taken organic chemistry, I’ve shown its atomic structure in the figure.

L-DOPA, aka levodopa, is an amino acid whose real name is L-dihydroxyphenylalanine. For those of you who have taken organic chemistry, I’ve shown its atomic structure in the figure.

L-DOPA is actually a precursor to dopamine, which means it can be converted into dopamine in the brain. When a person takes L-DOPA, it gets absorbed into the bloodstream and eventually crosses the blood-brain barrier to reach the brain. Once in the brain, it is converted into dopamine, which helps to replenish the dopamine levels and improve the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.

This is the description that you read on most Parkinson’s sites. However, it needs some clarification and additional information. Particularly, if you don’t have. degree in biochemistry. The first issue is a minor one. What is that ‘L’ in front of the name?

Many organic chemicals come in two forms that are mirror images. Like right and left handed gloves. And like gloves, it’s hard to convert one into the other without some serious surgery. DOPA also comes in two mirror image forms. One is called ‘L-DOPA’, the other D-DOPA. Your body makes only the L form and it is the only form that can be converted into dopamine.

The second issue has to do with the conversion of L-DOPA into dopamine. L-DOPA by itself isn’t very useful. It’s the chemical change into dopamine that’s critical for Parkinson’s relief. So why don’t we take dopamine directly? Why go through the hassle of taking something that must be converted into dopamine?

The answer is that dopamine can’t get to the brain where it’s needed. There’s something called the blood/brain barrier that prevents many chemicals from passing from the blood stream into the brain. L-DOPA can pass this hurdle. L-DOPA gets across the blood/brain barrier with the help of a special protein that transports many amino acids into the brain.

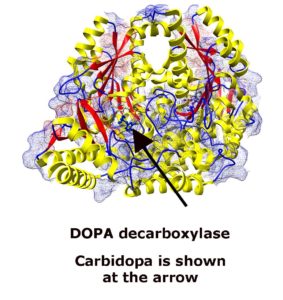

What happens when the DOPA gets to its intended target? In the brain, and in other nervous tissue, there’s a tiny chemical machine, an enzyme, that does the conversion to dopamine. It’s called ‘aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase‘ or ‘DOPA decarboxylase’.

However, there is a challenge when using L-DOPA alone. When it is taken by itself, a significant amount of it is converted into dopamine outside the brain before it can reach its target. This can result in unwanted side effects, like diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting, and a diminution in the effectiveness of the medication.

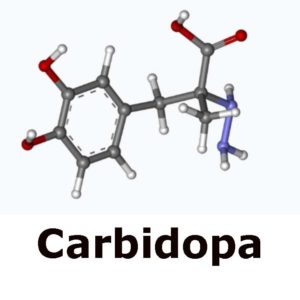

This is where carbidopa comes in. Carbidopa is another amino acid that is often combined with L-DOPA in Parkinson’s disease treatment. Carbidopa does not convert into dopamine like L-DOPA does, but it plays a crucial role in the treatment.

This is where carbidopa comes in. Carbidopa is another amino acid that is often combined with L-DOPA in Parkinson’s disease treatment. Carbidopa does not convert into dopamine like L-DOPA does, but it plays a crucial role in the treatment.

Carbidopa works by inhibiting DOPA decarboxylase. You can get an idea how it does it by examining the picture below. Notice that it has infiltrated the enzyme. In that position, it interferes with the conversion of DOPA into dopamine. However, that doesn’t seem to make any sense. Why would you want to prevent the conversion of DOPA into dopamine? After all that’s why you’re taking DOPA in the first place.

The answer is that carbidopa inhibits the conversion of DOPA into dopamine only outside the brain. It, like dopamine, can’t cross the blood/brain barrier. By inhibiting DOPA decarboxylase outside of the brain, carbidopa helps to prevent the breakdown of L-DOPA into dopamine before it reaches the brain. As a result, more L-DOPA is available to cross the blood-brain barrier and be converted into dopamine specifically in the brain, where it is needed. This allows for a higher concentration of dopamine to be restored in the brain, leading to improved control of movement and reduction in Parkinson’s symptoms. At the same time, it ameliorates the unwanted side effects of dopamine when its present outside of the brain.

So, to summarize, L-DOPA is converted into dopamine in the brain, replenishing the low dopamine levels in Parkinson’s disease. Carbidopa is added to the treatment to prevent the breakdown of L-DOPA into dopamine outside the brain, ensuring more L-DOPA reaches the brain and improving its effectiveness while minimizing side effects. Together, L-DOPA and carbidopa thereby help to alleviate the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease and improve the quality of life for people living with this condition.