Symptoms and MSA

9/6/24

A list of Issues

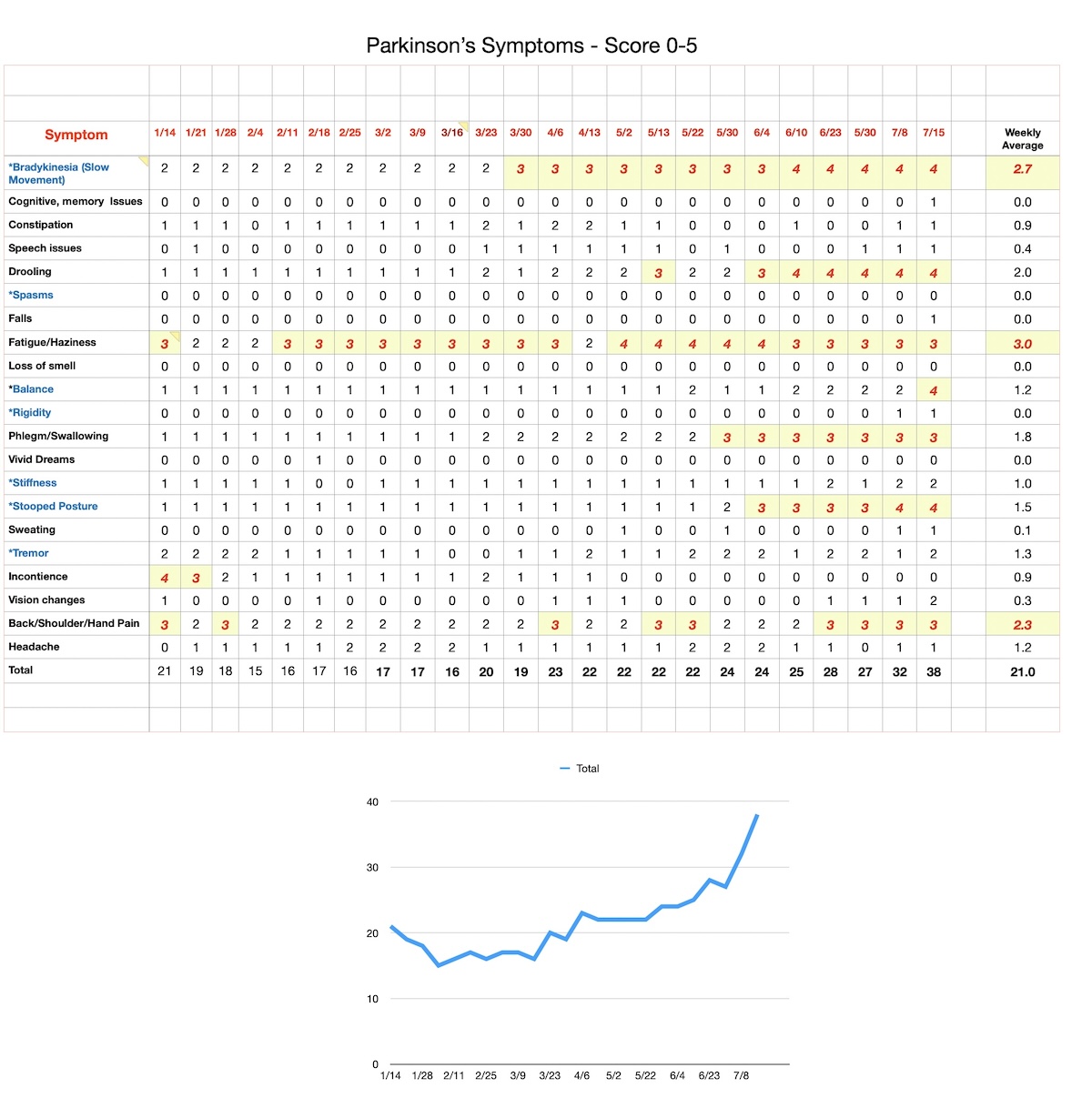

What’s the value of making a list of the symptoms that I’ve been experiencing after a year and a half of suffering from Parkinson’s? For one thing, Parkinson’s is a disease with a host of issues that varies from one individual to another. A comparison of my problems with someone else’s may be valuable in distinguishing Parkinson’s symptoms from some other difficulties. A more pressing reason in my case, has to do with another disease that I may be afflicted with: multiple system atrophy (MSA).

MSA is a disease whose manifestations are very similar to Parkinson’s. In fact, it is extremely difficult to distinguish between the two disorders. One distinctive feature is that MSA doesn’t usually respond to carbidopa/levodopa therapy and that’s what seems to be happening in my case. And that’s why I’ve become interested in it.

So what is MSA and how does it differ from Parkinson’s? Like Parkinson’s, MSA is a neurological alpha-synucleinopathy (alpha-synuclein clumps are often observed in brain tissue) in which one’s brain cells die over time. Even for experts, it’s difficult to distinguish between the two diseases. It’s a less common disease characterized by faster progression. And, like Parkinson’s, there’s no cure. However, MSA affects autonomic functions much more than Parkinson’s. The result is that swallowing becomes more difficult. Blood pressure is less well controlled (standing up suddenly can result in a rapid drop in blood pressure), and urinary and bowel dysfunctions are more often observed.

If I had a choice between the two diseases, I would choose Parkinson’s over MSA. Rapidity of progression and reduced time to death are important factors. But I have no choice. Regardless of the disorder that I’m afflicted with, below I list the symptoms that I’m currently experiencing:

- Weakness on my left side.

- “Pisa syndrome” – body leans to the right when seated or standing.

- Difficulty changing position in bed.

- Drooling.

- Accumulation of mucus in my throat when lying on my back.

- Lack of dexterity when using my left hand – difficulty with typing and with buttons.

- Slowness of movement. Short steps.

- Inability to swim using the crawl.

- Frequent loss of balance.

- Constipation.

- Lack of energy, lethargy, fogginess.

- Tremors.

- Worst of all, my golf game has gone to pot.

On the positive side, as I can tell I have no cognitive issues and my ability to smell seems normal. According to my neurologist, these symptoms don’t allow for a definitive diagnosis of MSA, but they don’t rule it out. The only way to be sure is to do a brain section upon autopsy. I probably will not be interested in learning the results when that happens.

In time, the likelihood is that some or all of these issues will get worse. I’m not looking forward to it.

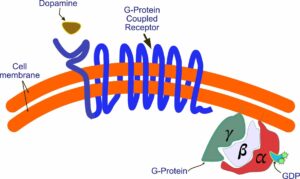

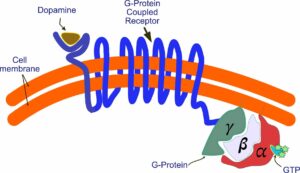

The G protein breaks apart, releasing the alpha subunit. It now interacts with components in the interior of the cell. One such component is an enzyme called adenyl cyclase. This enzyme becomes active and begins synthesizing cyclic AMP, an important molecule that interacts with a whole series of other molecules, influencing a variety of physiological processes. This, of course, is a simplification—not the whole story by a lot. For example, there are five different dopamine receptors—D1 through D5, all of which do different things. The process itself is also more complicated than I’ve shown. You can get a more detailed picture by going to the Wikipedia entry under G protein-coupled receptors.

The G protein breaks apart, releasing the alpha subunit. It now interacts with components in the interior of the cell. One such component is an enzyme called adenyl cyclase. This enzyme becomes active and begins synthesizing cyclic AMP, an important molecule that interacts with a whole series of other molecules, influencing a variety of physiological processes. This, of course, is a simplification—not the whole story by a lot. For example, there are five different dopamine receptors—D1 through D5, all of which do different things. The process itself is also more complicated than I’ve shown. You can get a more detailed picture by going to the Wikipedia entry under G protein-coupled receptors.