Beginnings

They used to call me Billy.

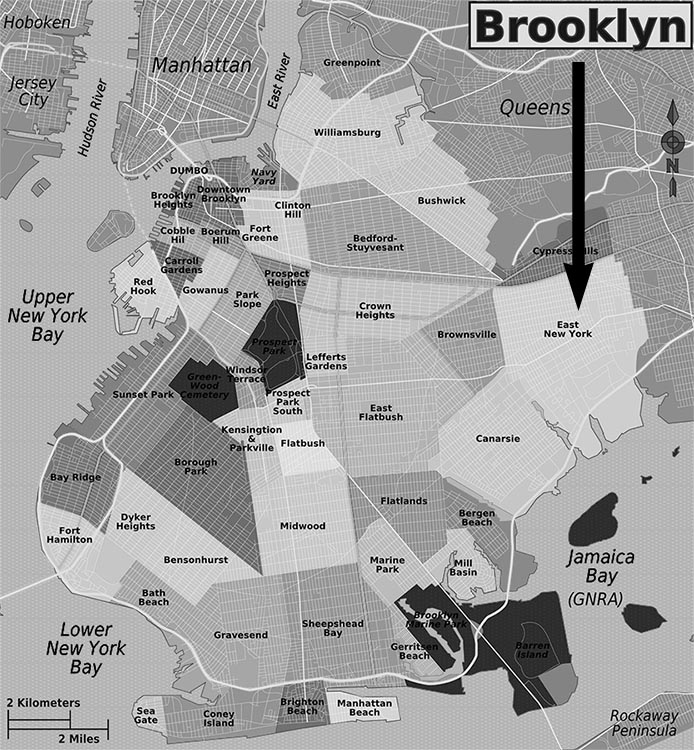

I was brought up in the East New York section of Brooklyn, notorious for being the principle dumping ground for victims of the mob. Bodies bearing evidence of cement boots would regularly wash up on the shores of Jamaica Bay, a great salt marsh blanketed with five foot high reeds atop black mudflats. It was only a few miles from where I lived. Few ventured into this quagmire. A corpse could forever rot undisturbed there. Not that I ever encountered any mobsters, or their fatalities for that matter. Ours was a quiet mostly Jewish community with London plane tree-lined rows of modest four family brick houses separated by narrow alleyways. My home was near the end of the street, the closest one to the “el” – an elevated section of the old New Lots IRT line – that snaked from Manhattan through Brooklyn and back, terminating a few stops away. Beyond the last stop was a depot where sleeping trains were garaged in anticipation of the morning and evening rush hours. A few trains would operate all night, brightly sparking and loudly squealing as their metal wheels clattered over the tracks. I had become accustomed to their racket just outside my bedroom window. It was only when I was 15, having left home for the first time for a summer job in the Catskill Mountains, that I realized that this daily clamor wasn’t universally shared. All that summer it was the quiet that kept me awake.

Map of Brooklyn

The East New York section of Brooklyn is shown under the arrow.

My grandfather, Osher, whom we called by his Yiddish title, zayde, was the patriarch of the family. He was the owner of our building, a two story row house with four cramped apartments, a dimly lit hallway, deteriorating linoleum covered stairs that steeply climbed to the second floor, and a dark, damp basement with rough unfinished stone walls and two abandoned coal bins. It had been deeded to him by a shady character who owed my grandfather a considerable sum and, having run afoul of the law, exchanged the house for the debt. Zayde proceeded to move his family – a wife, two daughters, a son who suffered from a severe birth defect, and my father – from a tenement on Broom Street on the lower East Side of Manhattan to what was effectively the suburbs.

The contrast with their former home was striking: only one flight of stairs; no pushcarts; each apartment with its own bathroom. It was a significant step up. My aunts and their husbands occupied two of the apartments, one on the first floor front and the other on the second floor rear. Zayde and his wife, my Bubbie, as well as Jakie their son, lived upstairs facing the street.

Despite the odors, in laws, chickens, and my mother’s continual complaints, my parents remained in my zayde’s house for 14 years. They didn’t move because they couldn’t afford to. The rent, subsidized by my grandfather, was $28 per month, a small sum even in the 1940’s. Another reason to remain in place was the house’s easy access to the city. The nearby elevated line, which we inappropriately called the “subway”, only became subterranean several miles from our home as it made its way westward into Manhattan where my father worked. For a dime, he could get to his job – he was a furrier – in 40 minutes. When we eventually did leave, we moved just a few blocks south into a single family row house newly abandoned by a recently arrived Puerto Rican family. Although there were plenty of traffic noises coming from Linden Boulevard, a major thoroughfare a half block away, I missed the sounds of the trains. But not the smells.

When my father got married, he and his new bride moved into the ground floor apartment in the rear of the building. It looked out on to a weedy, garbage-laden yard facing the back of several three story buildings twenty yards beyond. My mother never forgave him. She had grown up in the distant hills of the Bronx – the northern most of New York City’s five boroughs – in an apartment with her widowed mother and three sisters. Now, not yet twenty, she was suddenly confronted by two sisters-in-law and a mother-in-law, all in close proximity, all eager to offer advice to a newlywed. On the whole, my aunts were kind and helpful, but Bubbie and mom argued all the time. Their biggest conflict was over Bubbie’s standard of cleanliness, or lack thereof. The whole house smelled of the filth that emanated from the upper floor. The stench was compounded by the fact that at regular intervals a half dozen ancient fowl that were gifted from Bubbie’s brother’s chicken farm in New Jersey would be scampering around a cage in the small space alongside the stairwell that led to the roof. They were, after proper dispatching and plucking, destined to become the center piece of holiday celebrations. The holidays were also occasions when a live carp could be found swimming lazily in my grandparents bathtub. It didn’t smell, but I often wondered whether my grandparents shared the bath with the fish or just didn’t bathe while the tub was being otherwise employed. Dirt was my mother’s mortal enemy; she kept our apartment in immaculate condition. It was embarrassing to have guests over because of the miasma that emanated from above.

Mom

Henrietta Sofer (né Warshofsky) on stoop in Brookly, circa 1940

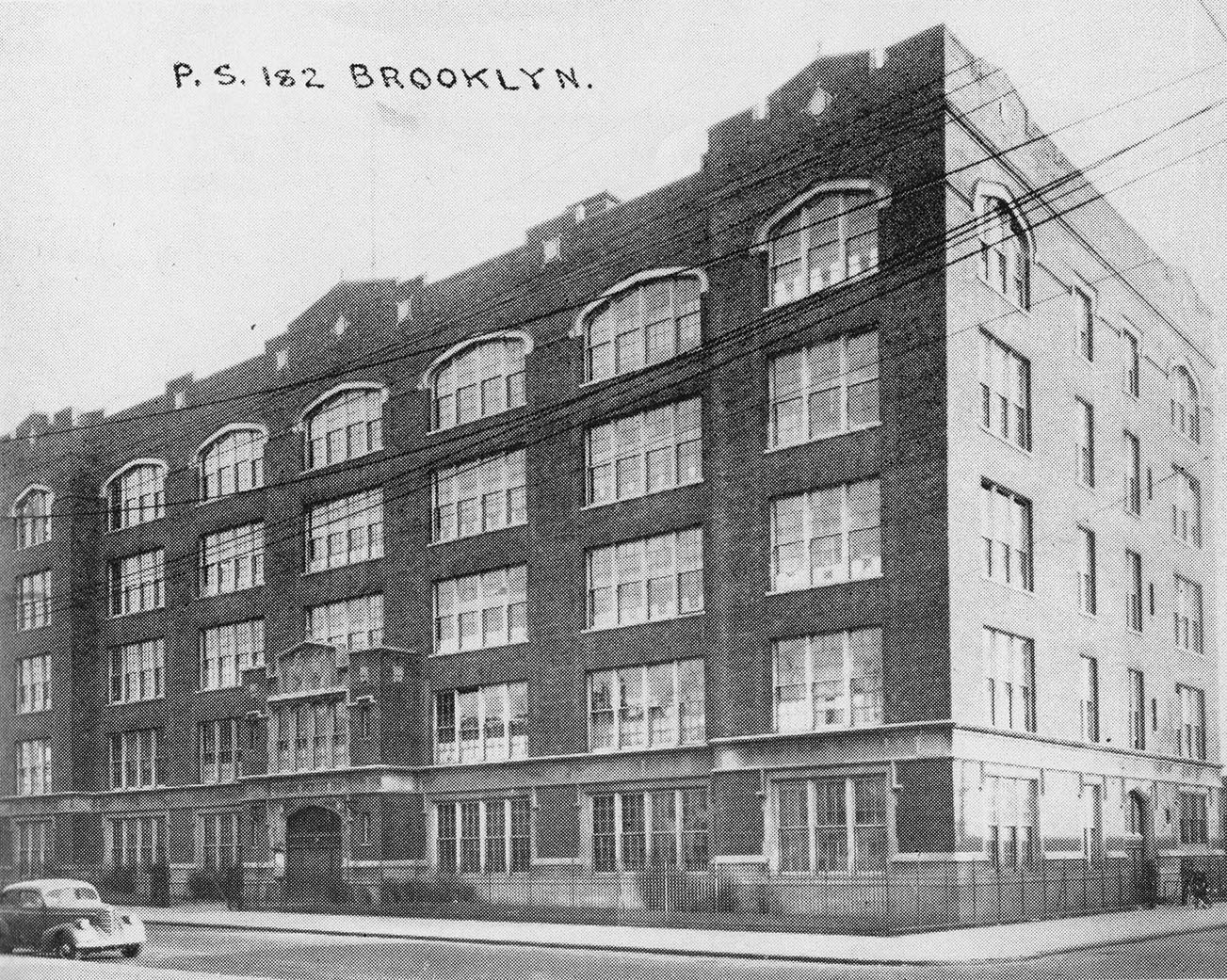

PS 182

Where I spent the first through sixth grades

At the age of six I enrolled in elementary school. PS 182 was an imposing five story building two blocks from my house. Adjoining it was a large concrete schoolyard where we would play punchball. And next to it was a garden of equal size where futile efforts were made every year to grow a series of sickly shrubs in the hard packed soil. Isaac Asimov and the comedian Phil Silvers, are well known alumni. For reasons that I can’t recall, my parents didn’t send me to kindergarten, and I began my scholarly career in first grade. Mrs. Tuttle, a kindly gray haired matron, greeted me and my mother at the door to my classroom. She addressed us with a gentle smile. “Welcome”, she whispered. Then she turned to the students already seated at their desks. “Class this is William”. Puzzled, I looked around to locate the object of her introduction. No one had ever called me William before.

A group of about a two dozen of us had been judged “gifted” by virtue of an IQ test. From the second grade until graduation, so branded, we remained together year after year. We grew to know each other well, each kid having a place in the hierarchy that develops when people are grouped together for a long time. Steve was the acknowledged leading intellectual in our classes, at least among the boys. He was to be my classmate throughout elementary school, junior high school, college, and graduate school (he moved to a more upscale neighborhood after junior high school, so we didn’t attend the same high school). There were a number of other bright kids in the group. But prowess in the classroom and grades were not the major way we judged each other. Athletic ability was the coin of the realm. Jerry Goldstein was tall and lean, and excelled in sports, and was universally admired. I probably stood in the upper third of the class academically, but I was never any good at punchball, stickball, or basketball, the games we played in the schoolyards and streets of the neighborhood. It was one of my major disappointments as a child.

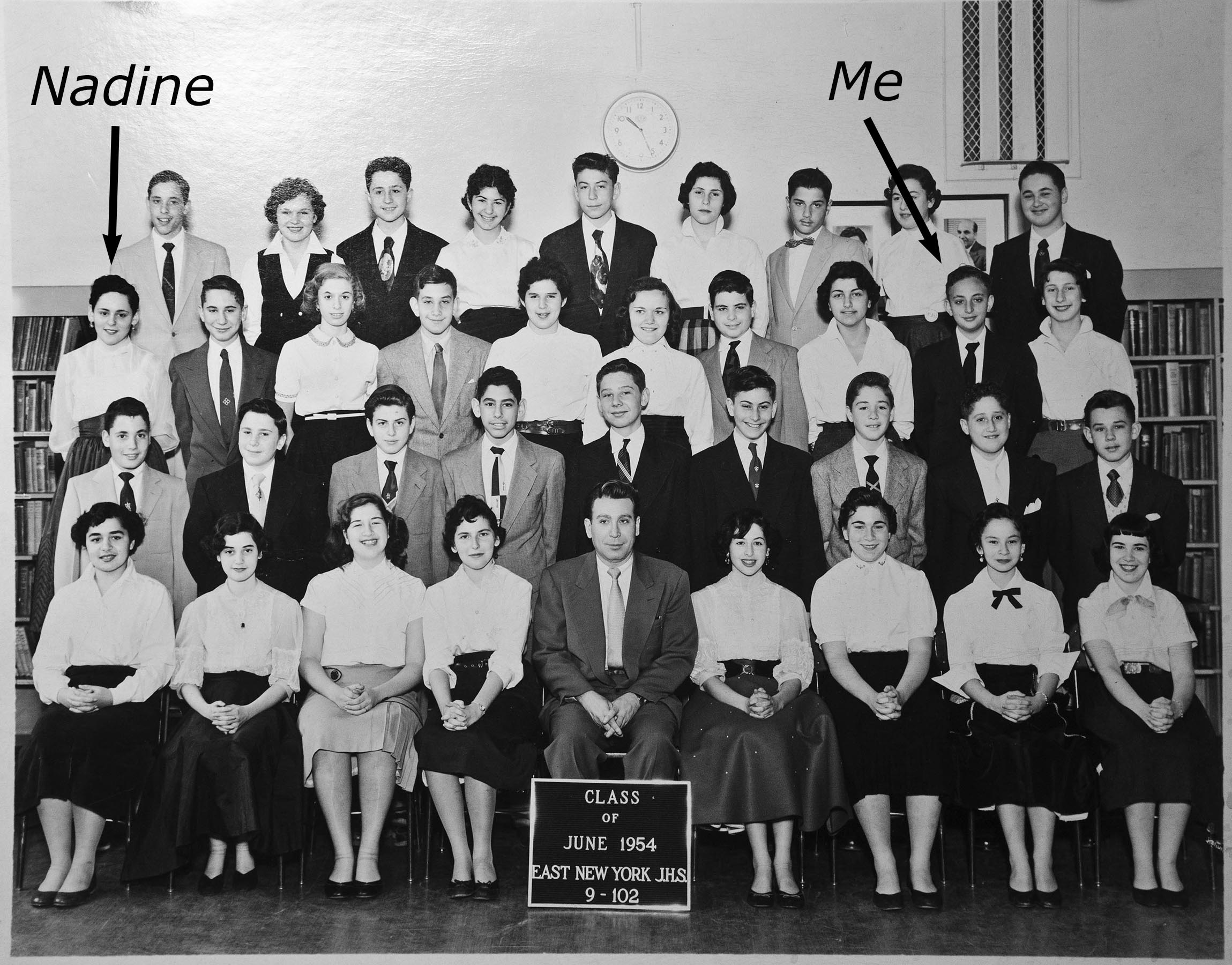

My days at PS182 were a mosaic; happy moments interspersed with anxious ones, successes mixed with disappointments. Some of my happiest remembrances are of an amorous nature. Because I loved to read, the fairy tales and stories of noble knights and princesses that I devoured as a child primed me for romance at an early age. So naturally, when the opportunity presented I fell in love. It was the second grade. Her name was Nadine. She had dark curly hair and a captivating smile. She was smart, cultured, with a soft voice, and an artistic bent. I would daydream of her while sitting at my desk in school and when I went to sleep at night, imagining myself rescuing her from danger, defending her from schoolyard bullies.

Because Nadine was also among those judged to be above average intellectually, we moved from grade to grade together: we were in the same class throughout elementary school. All through this time, I remained smitten. But despite our daily close proximity, ours was a distant relationship. In all the years that we shared the same classroom, I don’t remember speaking to her once. We certainly never had a long meaningful conversation. It wasn’t only because I was shy. Rather I thought of her as royalty: inaccessible, on a pedestal. I felt unworthy of such a creature. She must have known that I was enamored of her – I regularly stared at her with a lovesick expression – but because I never overtly expressed my feelings, she didn’t really acknowledge me.

However, one day in the fourth grade on the sidewalk outside the school, for reasons I don’t remember, in an unpremeditated gesture that surprised me as much as her, I snuck up beside her and kissed her on the cheek. Of course, I immediately ran away, laughing as only a nine year old full of himself and who had done something slightly naughty would do. This didn’t change our relationship, at least not at first – the incident never was really acknowledged between us. But a few months later, near the end of the school term, while I was seated at my desk while daydreaming about playing shortstop with the New York Yankees or some other impossibility, Nadine and Belinda approached. It soon became apparent that they were having a dispute. And it was over me! Belinda insisted that I “liked” her. Nadine countered that she was the object of my affection, and, as proof, bragged that I had actually kissed her. Belinda didn’t believe it. She was petite, vivacious, and a ball of energy and felt – with some evidence – that all the boys were attracted to her. She wasn’t to be outshone by anyone, even if she didn’t particularly care for me. The two stood before me at my desk in order to resolve the issue.

I don’t remember how I responded or even how the episode ended. I do recall with some shame that I felt proud, not so much because it demonstrated that Nadine had returned my affections, but because I was being sought after by two of the most attractive girls in the class.

My ninth grade class

JHS 149

My entirely platonic relationship with Nadine ended in the ninth grade. We continued to be in the same elementary school classes for two more years, a period covering the fifth and sixth grades. When we graduated, still tethered together by a bygone IQ test, we attended the same junior high school, JHS 149, and were placed together in Mr. Goldman’s rapid advance class, meaning that we were selected to skip eighth grade. As before, we hardly spoke during this time, but I still harbored romantic notions. When we were nearing graduation day, I summoned the little courage I had, and asked her to the senior outing. All the students were to take the subway to Coney Island and eat hot dogs and ride the roller coaster. She said yes. But on the day before the event, she informed me that her mother had forbidden her to go. Apparently her parents thought she was too young to go out on a date with a sophisticate like me. They must have thought that I would take advantage of her. It was a major blow. And even though Nadine and I later went to the same high school, and ultimately even to the same college, being stood up broke our connection forever thereafter.

A particularly painful experience occurred in the fourth grade. Mrs. Schwartz had assigned one student in each row to check a daily log – a brief entry in a dedicated notebook that we had to enter concerning the happenings of the previous day. She picked me. It was a permanent job, lasting the entire academic year. Having been awarded that assignment, each morning I would stalk along the line of desks, each with an unused inkwell and engraved with the initials of previous inhabitants, and inspect the handiwork of each student. I took the job seriously and was strict with miscreants who had written only a sentence or two, reporting them to our teacher. However, sometime early in the fall, after less than a month or so of classes, I began failing to record anything. After a while, the missing entries became an everyday occurrence. My conscience began gnawing at me, but I was unable to bring myself to fill the empty spaces in the notebook with imaginary texts. I was certain that my feeble attempts to make up comments about the weather or family life would be detected as fake.

We went on a family holiday that fall, an unusual event since my father usually couldn’t afford to miss work. In our black 1949 Pontiac with its silver stripes down the front and back, we wended our way south from Brooklyn through New Jersey, along the route of the

A Pontiac. This photo is of the 1950 model. Ours looked much the same, black, with a native American logo pointing the way. soon-to-be-completed Jersey turnpike, through Delaware, and Maryland. Our destination was Front Royal, Virginia, where the Skyline Drive began, the entry to the Shenandoah National Park.

It was a wonderful experience, the first real adventure away from home that I can remember (other than our trip to Florida, an adventure of a completely different kind, see “Florida and Guns”. We drove along the Skyline Drive and visited the Skyline Caverns. We slept in sleazy motels, climbed incredibly green mountains, and hiked along the park’s trails. We saw wondrous creatures: deer, chipmunks, snakes, and salamanders. We breathed air that bore none of the acrid odors that permeated Brooklyn. It should have been idyllic. But at night I battled my conscience. I was obsessed with the daily log. I knew I had cheated and I was certain that I was going to pay the price. Mrs. Schwartz would collect the notebooks at at any moment and my sins would be revealed for the world to see. It bothered me so much that one night I woke up screaming. My father tried to comfort me, but I was inconsolable. What I had done was so terrible that I couldn’t admit it to my parents or to anyone else. I was miserable.

In the weeks following, I made some feeble attempts to fill the notebook, but the entries were unconvincing, even to me. In the end, Mrs. Schwartz didn’t collect our work, even though I lived in fear for many months. When the spring term ended, she announced that she was honoring four students for their academic achievement, two girls and two boys. Steve and Regina came in in first place. Nadine and I placed second. I reacted badly. Not because I had failed to come out on top. – I was well aware that Steve was the superior student. It was the notebook. I had cheated, not been caught, yet I had been rewarded. And undeservedly so. Guilt is a cold shower that can rain on the brightest of spring days.